Why and How to use Version Control: A Simple Git and GitHub Tutorial

26 Dec 2018

. category:

code

.

Zero Comments

#code

#tutorial

Last Updated January 29 2019

In this simple git tutorial I will try to explain as simply as I can, what version control, Git and GitHub is, and why you should use them.

I will go over the basics and only a few more advanced points in this article.

In this tutorial I will be using the the command line git commands, so I will assume that you know how to use the command line, and I will go at a fairly fast pace.

What is Git?

Git is a version control system. In this article, I will focus on Git, which is the most popular version control system.

Version Control is a piece of software that helps teams or individuals manage their source code over time. It tracks changes in a project so that if something breaks while you are working on it, you can compare the difference between the current project and a previous version of the project. You can even “checkout” a previous version of the project and make changes to it. Also, with Git you can have separate “branches,” which are separate, parallel “versions” of the project that can be worked on simultaneously. For example, one member of a team can work on a feature at the same time as another person (or the same person) works on a different feature. Once the features are finished, they can both be (hopefully seamlessly) be merged back into the main branch (called the master branch). There are also many, many other features of Git, some of which I will talk about in this tutorial.

What is GitHub?

GitHub is mostly a Hub for Git projects. That is, it is a platform that interfaces with Git to store projects that use Git in the cloud. It is useful for when you have multiple people or computers working on the project, because people can easily update their version of the project with a simple Git command. GitHub is also useful for ensuring that you have backups of your project, because if your version gets deleted you can just clone the entire project, including the entire history of the project, from the GitHub cloud.

Sign up for a GitHub account at github.com. Paid accounts allow you to make your projects private. Unless you want to start a very private project you don’t need a paid account (Duh). If someone else invites you to work on their private project, you do not need a paid account to work on their project as a collaborator. If you are a student or teacher you can sign up for a free paid account after you sign up for a standard account. (UPDATE: GitHub now has free private repositories. See this blog post)

This website’s source code is published and served from a GitHub repository. Click the “source” button at the bottom of this page to find it.

Why use Git and GitHub?

First of all, once you start using Git and GitHub, you’ll never stop using it.

With Git and GitHub, you can easily:

- Keep track of your project’s history, so you can revert back to an older version if the current version is failing, or if you need to use or compare code from an older version.

- The whole entire project history is stored within your project, in a folder named

.gitIt is very hard to lose code with Git. - Manage different versions. You can even tag different versions with tags like “

v1,v2.0.01b,b4, etc.” and then you can easily checkout the tagged versions. Or else you can make “releases” on GitHub and then easily link to different releases from your website/wherever. - Collaborate with others. Collaboration, or at least the basics of collaboration features, is easy with Git and GitHub.

- Keep different branches. With different branches, you can, for example: have different branches where you work on different features; have one branch for, say, the Python version of the project and one branch for, say, the Ruby version of the project, have one for the documentation, and one for the website…

- Easily duplicate any version of the project into a different branch, make changes, and then merge it back into the original branch.

- Git is extremely fast

- Keep backups of your projects on GitHub - although this is a benefit of using GitHub, don’t start thinking of Git as a backup system, as that is not what it is.

- Keep track of your project’s issues and bugs on GitHub.

- Publish or store your source code on one of the world’s leading software development platforms: GitHub.

- Have one place online where you keep all your code, and all of its history, collaborators, documentation, etc.

- Git and GitHub is one of the most popular version control systems.

- Tons of other things.

The Basics

Make sure you have Git downloaded and installed and are logged into your GitHub account. Start your command line and test git by running $ git

Also, you will obviously need a project to experiment on. You could start with just a blank directory (folder) and create a text file hellogit.txt. Then you could just add some text to it.

Setup

Method 1: create a new Git & GitHub project

To turn an ordinary directory into a Git project, open up the command line, cd into the project directory, and run the following command.

$ git init

Git will initialise a folder named .git in the root of your project directory. Git will story the project history, branches, configuration, etc. in this folder.

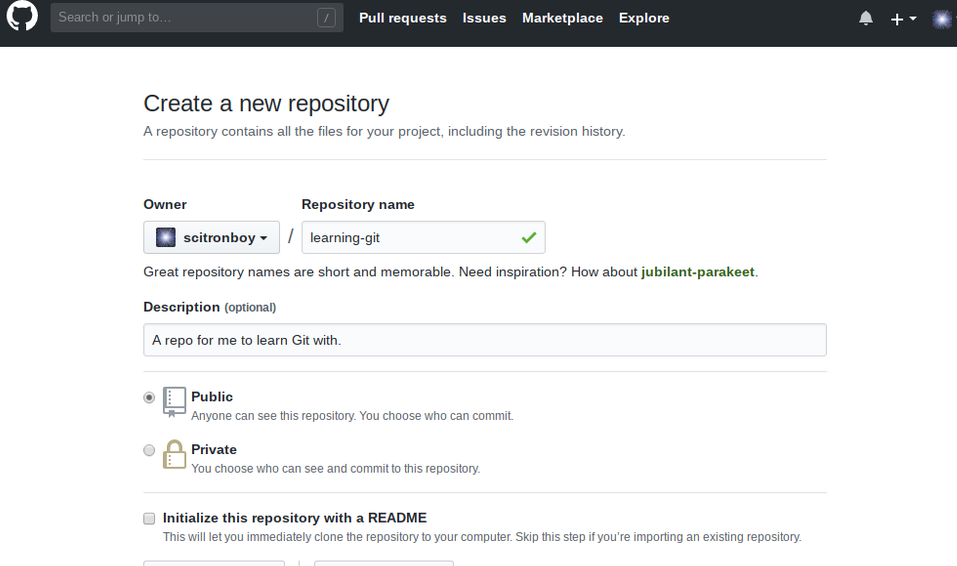

Now we need to set up the remote copy of the project on GitHub. Go to github.com and click on the little plus icon in the top right. Click “new repository.” Fill out the repo details like in the picture then click “create repository”

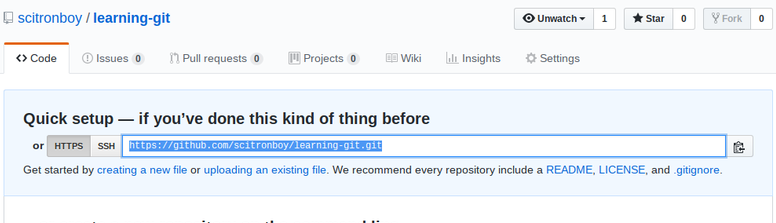

Then copy the URL at the top of the next page, and switch back to the command line.

Now we need to tell our local Git project where the remote project is. Git calls the remote project URL the “origin,” so we need to run this command to set it up:

git remote add origin <URL>

Replace <URL> with the URL you copied from GitHub. We are now finished setting up a new repo with Git and GitHub.

Method 2: Clone an existing GitHub project

If there is an existing project you would like to download from github, open up your command line and cd into a directory where you’d like to store the project on your computer. Then run the following command:

git clone <URL>

Replace <URL> with the URL of the pre-existing project on GitHub.

Git add, commit, and push

Pay attention now:

Git works by taking “snapshots” of your project whenever you issue the “commit” command, which are saved as your project’s history. Don’t worry - Git doesn’t record the whole project every time you commit: it uses references to previous files in its snapshots, and it also compresses them. The actual history folder stays quite small. The three “levels,” or “trees,” of a git project are:

The “working directory”: This is just the directory (folder) that your project is stored in. You make changes to the code in this directory.

The “Index”, or the staging area: This is where you add stuff to be committed. This is stored in a file in the .git folder. Think of it like a stage: you can use the git add command to add files from your working directory to the stage, where they are prepared to be committed. Then you can use the commit command to take a snapshot of everything on the stage and store it in the project’s history.

The “HEAD”: This is just a reference to the previous commit or checkout in the current branch.

Then there is the remote origin, which refers to the remote copy of your project which is stored on GitHub. You can use the git push command to update the remote repo with any recent commits.

Try it Out

Let’s say you have some modified or new files in your working directory that you want to commit. First we can add the files to the stage, or Index:

$ git add <filename> will add just one file to the stage

$ git add . adds everything to the stage - you will use this most often as it will add all changes and additions throughout your project to the stage.

Now we use commit to take a snapshot of the changes that are staged and send them to the HEAD. Every commit also needs a unique commit message that identifies in less than one sentence what the changes were. The commit message might be something like “fixed broken navbar”, “added main menu error catcher”, or “added steering”. In this example we will make the message “first commit,” because this is our first commit in this repo.

$ git commit -m "first commit"

The first time you commit, it might ask you to setup your name and email with the config command.

Now we need to push the changes to our remote repo on GitHub. The first time we do this we must specify which remote origin “upstream” we would like to use. Since we are still on the default branch, the master branch, we add -u origin master.

$ git push -u origin master

It might ask you for your GitHub username and password - just fill them in and press enter (you won’t see your password being typed, but that’s just a safety feature).

In our future pushes to the remote master branch, we do not need to specify the upstream:

$ git push

Note that git push only pushes changes in the current branch (master).

Branches

Branches are like different copies of the working directory that can be modified separately and then merged together into one branch. One example of when you would use branches is for writing drafts for this blog. Usually, when I am writing a post, it takes at least a few days and during that time I might want to make other changes to my website. But if I’ve started working on a post, I don’t want to publish a half-finished post along with the other change. The solution is to create a separate branch at the time when I start writing my draft. I then write the draft in the new branch, and git records the changes. I am free to make and commit changes in my master branch because my draft is safely stored away in my draft branch. When I am finished writing my draft, I merge the draft branch into the master branch, which adds the commits from the draft branch onto the commits in the master branch.

Git status

Use the git status command to see what branch you are on:

$ git status

Create, merge, and delete a branch

if you are on the master branch, run the following command to duplicate the HEAD into a second branch:

$ git branch branch2

Branch branch2 is now identical to branch master. Run the following to checkout, or “move into”, the new branch:

$ git checkout branch2

Create a new file (for example hello2.txt) in the working directory. Add and commit the changes. Then push this branch’s changes to the remote origin. Remember, this is the first time pushing this branch, so we must specify its upstream with -u origin branch2.

$ git push -u origin branch2

Let’s “merge” the changes into the master branch now. First change back into master branch, then merge:

$ git checkout master

$ git merge branch2

Branch master should now contain the hello2.txt file.

Let’s delete branch2 now:

$ git branch -d branch2

Conflicts

Sometimes there are conflicts and auto-merging does not work. For example, in two branches you might have a file a.txt, and you might add “Adam” to the first line in one branch, but someone adds “Bob” to the first line in the second branch. Git wouldn’t know whether you wanted “Adam” or “Bob” on the first line. If this happens, git will tell you that you must fix the conflicts. To do that, just modify the files that it lists until you have them the way you want them to be. Then, mark the conflicts as resolved by adding that file to the stage. When you are done resolving the conflicts, commit the changes. You can also use git diff to view changes between two branches. For example:

File a.txt has different first lines in branch a and b, so merging results in a conflict. We can use git diff to see the differences between the two branches:

We can see that in branch b relative to branch a, Adam was removed and Bob was added to the first line. We decide that we want the first line to contain Bob, so we manually edit the file and change the first line to “Bob”. In fact, git automatically modifies the file and adds the differences to the file itself, so it is just a matter of deleting the lines we do not want. In fact, we didn’t even need to use git diff in the first place. After editing the file the way we want, we mark the conflict as resolved by adding it to the Index and then commit the changes:

$ git add a.txt

$ git commit -m "manually fixed merge conflict in a.txt"

Now the merge conflict is resolved.

Pulling changes from GitHub: fetch and pull

To update your local branch with the most recent commits on the remote origin branch, first change into the branch you want to update and then fetch the origin:

$ git checkout branchname

$ git fetch origin

then merge the remote branch from the origin that you just fetched into the local branch:

$ git merge origin/branchname

or else, to do both at once, do git pull:

$ git pull

Checking out previous versions with git checkout

Every file, directory, and pretty much everything else in Git has an unique 40-character hash, calculated from the contents of the object, that identifies it. These hashes help git to prevent data loss, because if git detects a hash mismatch between the actual file and its known hash, then Git will know that something went wrong. In git, commits are also given unique hashes. To checkout a previous version of the project, you must use the log command to list the log of commits and their hashes, then checkout the hash that you want.

$ git log will list each commit (in the current branch)’s hash and commit message. The hash will be something like 24b9da6552252987aa493b52f8696cd6d3b00373. To checkout that commit, which will temporarily revert your project to its state at that commit, you use the checkout command with at least the first six digits of the hash. Make sure you replace 24b9da with the first six or more digits of your commit’s unique hash:

$ git checkout 24b9da

Git will give you a message about being in a “detached HEAD” state. This just means that you are not on the HEAD, because the HEAD is the last commit, remember? and you just checked out a commit that was earlier in your project’s history.

To return to the latest commit in, say, the master branch, just checkout that branch:

$ git checkout master

A note about git log

As you may have noticed, git log lists every commit with about 5 lines. If you do not need the extra details, you can run this command so that, in the future, git lists every commit on just one line:

$ git config format.pretty oneline

Also, press q at any time to close the log, and press enter or return to scroll down through a long log file.

One more thing: you can have git generate a “tree” that shows all the branches and merges with this command:

$ git log --graph --oneline --decorate --all

And you can see lots more log commands in the official docs or by typing git log --help.

Saving changes made in previous commits

If you checkout a previous commit and make changes to it, you can save the modified working directory in a new branch by running:

git checkout -b branchname

This will create a new branch that contains the project at that point in time, and it will also checkout the new branch for you.

A bit more advanced stuff

Reflog basics

You can use git reflog, which stands for “reference log”, to show the history of where the HEAD was or where another branch’s HEAD was. This can be used, for example, to recover lost commits.

$ git reflog will show the history of the current branchs HEAD. It contains commits, checkouts, merges, resets, reverts, etc, along with their hashes. You can checkout any of the hashes to temporarily detach the HEAD and go back to that point in time. Just like always, you can checkout the most recent commit with git checkout branchname or git checkout HEAD

To show the history of another branch’s HEAD, use this:

$ git reflog show branchname

Tagging

In git, you can tag certain commits with custom ids. For example, you could tag each finished version with a tag like v1.0.0, etc. Tag a commit with git tag tagname commithash. Here’s an example:

$ git tag v1.0 24b9da6552

Then we could easily checkout commit 24b9da6552 by using the tag instead of the hash:

$ git checkout v1.0

You can view all tags like this:

$ git tag

More useful tips

The .gitignore

When working on a project, it is usually easiest to use the git add . command to add all changes in all files to the Index all at once. Sometimes, though, there will be files that you never want pushed to GitHub or even committed. Some examples are custom config files, credentials files with private information, virtual environments, swap files, os-generated files (such as .DS_Store on mac), log files, etcetera. To work around this, you can create a custom file in your project directory that contains files and folders that you want git to ignore. This file should be named .gitignore. Here’s an example:

Conclusion

That’s the end for now! I will add more advanced stuff to this not so simple git guide and tutorial sometime soon, like stashing, more on merging, resetting, how to make a pull request, reverting, etc…

You can find the official Git reference manual here, and you can also read the entire Pro Git book online for free.

Let me know in the comments below if you have any questions or suggestions, or else contact me or file an issue on GitHub. Thanks for reading!

If you liked this tutorial, please give it an upvote on hackr.io:

Thanks!