Make a fun HTML & JavaScript game - part 2: JavaScript tutorial

01 Mar 2019

. category:

code

.

Zero Comments

#web-dev

#game

#code

#project

#tutorial

In this tutorial series, I will guide you through the steps to create your own simple but fun online browser-based game, using HTML and JavaScript.

Click here if you want to see the game we will create. Remember that you will be able to customize your own however you want.

This is part two of the tutorial. If you have not read part one, you should read it now. Click here for part 1: HTML tutorial. Once you have read it, you can continue with this part.

In this part of the tutorial, I will show you how to add JavaScript to program the game itself. Keep in mind that this tutorial is meant for beginners (or almost-beginners), but I will only cover what is needed to teach you how to make this game. It may seem too complicated or hard at first, so if it does check out some of the links at the bottom and come back when you feel a little more comfortable with JavaScript basics.

I will include links at the bottom of this article to reference for every concept we use.

Here’s a reminder of what we did in part 1:

- We learned the basics of HTML, which uses

<tags>to tell the browser more about different elements on the page, for example the<i></i>tags that italicize stuff. - We learned how JavaScript can be added to websites to make them interactive or add other programmed functionality.

- We learned how to get and use a text editor, or code editor, which makes code look better. If you haven’t got one yet, now might be a good time to get one. (Or else you could use the online TryIt editor)

- And finally we created a simple web page for the game to live in. We used a

<canvas>element to create a “canvas” for the game.

Here’s the code for the web page so far:

Let’s start!

JavaScript Basics

JavaScript is put between <script> tags in a web page. Then, when a browser is loading a page, it reads the HTML line by line, and when it comes to a <script> tag, it knows everything from there until the closing </script> tag is JavaScript. So, it reads the JavaScript line by line and follows the instructions on each one. Here I will cover a few of the different things you can do on each line in JavaScript.

The semicolon

In JavaScript you should put a semicolon after every command. This tells the browser that the command is finished. This is not strictly required, but it is recommended. Here’s an example:

command;

do something else;

Keep in mind that there is usually one command per line.

Also remember that JavaScript ignores whitespace (spaces, indentation, new lines) so don’t be confused if my use of whitespace in the code throughout this article is inconsistent in places - because JavaScript doesn’t care so it doesn’t actually change the way the code runs.

Variables

Variables are a crucial part of most programming languages. They are simply a place where a program (the code) can store information, such as words, or numbers (think score, current location, whether or not a user has clicked a certain button, etc.)

Each variable in JavaScript has a name and a value. Think of them like boxes - each variable is a box that has a label written on the outside, and the computer can store numbers or other information inside the box. Then whenever it needs the information again it can look in the box. It can also change what’s in the box, if it needs to.

In JavaScript you declare (create) a variable by using an equals sign with the let keyword. (Please note: you may see other people use the var keyword in JavaScript. Know that var can also be used to create a variable, however it is generally better to use the let keyword for reasons I will not explain here. If you would like to know why, please leave a comment at the end of this article.) Here’s an example:

let score = 50;

In that example, we are creating a variable (like a box) named score, and setting it equal to 50. The semicolon signifies the end of the command. Then if the player got 20 more points, we could change the variable to 70. Note that, after the variable is created, we do not need to use let anymore:

score = 70;

Or else we could use a math operator (+, -, *, /) and set score to itself + 20:

score = score + 20;

Since score was 50, and 50 + 20 = 70, score now equals 70.

In JavaScript you can also have word variables, but you MUST put the word between two double quotes (“”). Words, sentences, and letters are called “strings” in programming (think of a “string” of letters):

let my_first_name = "John";

You can see in the last example that I didn’t name the variable my first name, I named it my_first_name with an underscore instead of a space. This is very important because variable names cannot have spaces.

You can also do “addition” with strings. Here’s an example:

let my_last_name = "Smith";

let my_full_name = my_first_name + " " + my_last_name

Now my_full_name is equal to John Smith because we created it from my_first_name (which was “John”) plus a space (“ “) plus my_last_name (which was “Smith”).

Functions

Functions are like commands that tell the browser to do something. There are many built in functions, and you can also create your own. In JavaScript, you can call (execute) a function by simply typing the command followed by two parentheses. The parentheses are used to pass (give) parameters, or arguments, for the function to use. Arguments are put between the parentheses, with a comma separating each one, like this:

function(argument_1, argument_2, argument_3);

For example, imagine a scenario where you have a function named eat that tells the computer to eat (yes, yes, I know computers can’t eat). But how does it know what to eat when you call the eat() function? You could create different functions for different foods, like eat_orange and eat_apple, but that gets clunky and is not a good solution, because you’d have to write a new function every time you added a food item. The solution is to pass the eat function an argument every time that tells it what to eat. An example:

eat("apple"); or eat("orange");

Then when the function receives the argument it processes it and figures out what to eat.

Just so you know, functions can also “return” numbers, so that when you call it, it acts like a number, or string, or other object. Here’s an example of using a function to set a variable:

let the_weather = get_the_weather();

The console.log command

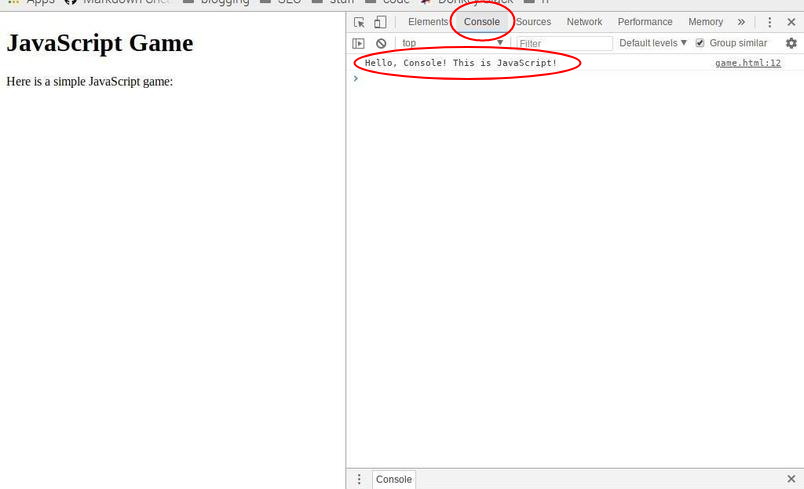

The console.log command is very useful for programming JavaScript. It can be used to send a message to the console, which is something that is integrated into most browsers that allows developers to interact with the JavaScript on a page. Try it out! Open up your game.html file and add this command in between the <script> tags:

console.log("Hello, Console! This is JavaScript!")

Load the page in your browser. Then open up your console. Usually, you can do this by pressing Ctrl+Shift+I or else right clicking the page and pressing “Inspect”. Then, click on “console” when the window opens. Here is an example on Chrome:

You can see the message at the top! That was generated by the little line of JavaScript we wrote!

Note: the log command is a function, however the console part is not actually part of the function name. It is instead a “class” that houses the log function. I will not cover classes in this tutorial, but just know that function names cannot actually have periods in them. Remember this when you start to create your own functions.

Creating your own function

In JavaScript, custom functions are blocks of code that are run when you call the function. They are often used when the same code needs to be run in two different places, because you can just call the function in each place instead of duplicating code. Here’s how you create your own function:

function my_own_function(my_own_argument) {do stuff using my_own_argument;}

You declare the function using the function keyword. Then, you name the function and add any arguments it will require to the parentheses. Then, you put all the code that will run when you call the function inside curly braces ({}).

Here’s an example of a function to print a full name to the console:

Then let’s say we have three names to print. Luckily we can use the name-printer function we just made to help us do that:

Here is the output (on the console):

Here is a full name:

Bob Joe

Here is a full name:

Margaret Joe

Here is a full name:

Jane Smith

Do you get it? We called print_full_name three times in that last script, and each time it printed the “Here is a full name” message and the full name which it pieced together using the arguments we passed it.

Don’t worry if this is a bit intimidating or confusing. It will probably become clearer later on. I also include links at the bottom to tutorials that you can use to learn more about JavaScript.

Game Overview

Before you start a project, it’s always a good idea to lay out a plan and figure out how you’ll do things before you start. So here’s how we want the finished game to behave:

- When you press the up arrow key, the game will start.

- The player will be a yellow (or any other color) circle

- There will be colored dots spread throughout the game

- The colored dots will move down the screen at a fixed rate so that it looks as if the player is moving forward

- The left and right arrow keys will move the player left and right

- The goal will be for the player to “fly” over as many colored dots as possible within the time limit. Each time the player flies over a dot, his score will increment by 2.

And here’s how we will build it:

- We will use the canvas to create the game graphics.

- We will create an

initfunction that will run when the page loads, that will add a message to the canvas that says “Press Up To Start” - We will detect key presses. The up arrow will trigger the start of the game, and the left and right arrow keys will trigger a function that moves the player left or right.

- We will create a game loop function that updates the game.

- The game loop function will move the colored dots down slightly each time it is run.

- It will also have a system to detect whether the player is over a colored dot, so that it can increment the score.

- Finally, it will erase the canvas, then draw the background, player, and score onto their new positions.

- We will make the game loop function run many times per second so that the game runs smoothly.

- Once the time limit is reached we will stop the game and display the final score.

Programming The Game

Now we will start programming the game.

Leave the console in you browser open the whole time, because it will alert you of any errors or problems in your code.

You will get an error near the beginning that says “init is not defined”. Just ignore it - we will fix it later.

Getting the canvas context

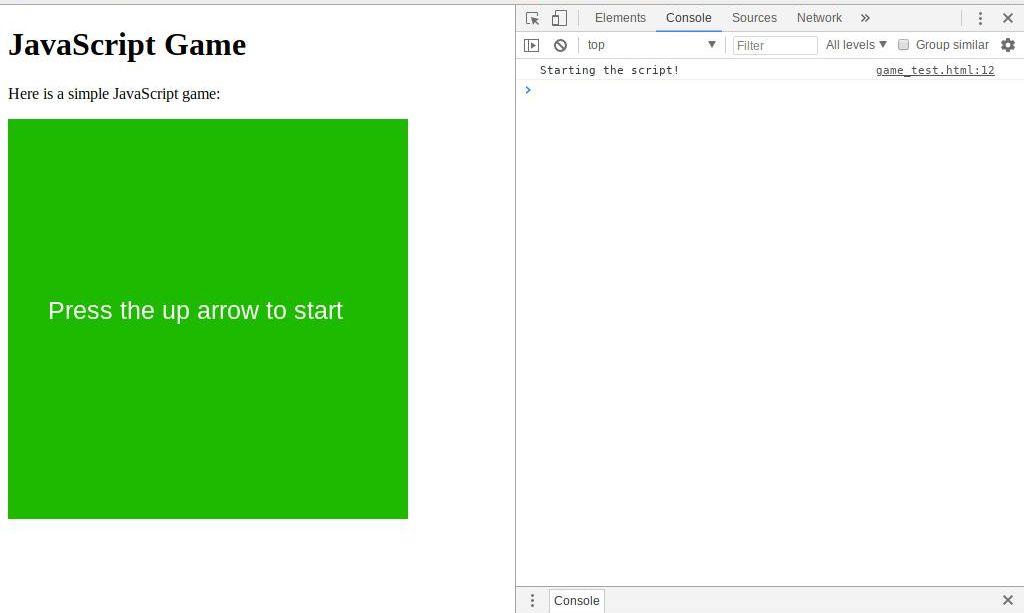

Let’s add a little message at the top of the <script> section in game.html so that we see in the console when the script starts:

console.log("Starting the script!");

Now the first thing that we need to do is to get a reference to the canvas on the web page, so that we can “draw” on it with JavaScript. Remember when we created the web page and we added a HTML attribute to the canvas that gave it an id? Specifically, id="c". Now we are going to use that id we added to tell JavaScript what we want. Add this to the top of your <script> section:

let canvas_element = document.getElementById("c");

document is a class that contains a ton of functions for accessing or manipulating the “document”, or the web page itself. getElementById is a function that gets a reference to an element on the page using its id. So when we call document.getElementById("c") JavaScript stores a reference to the element that has an id of c, which is our canvas.

Now we need to actually get the “context”, or the part of the canvas that will allow us to draw on it. To do this, we can use the getContext function of the canvas element:

let canvas = canvas_element.getContext("2d");

The argument 2d just tells getContext that we want the 2-dimensional part of the canvas.

A note about the coordinate system

When working with canvases, simple x and y coordinates are used. x is the horizontal axis and is the first argument in functions, and y is the vertical axis and is the second argument in functions. Each unit is 1 pixel. Remember that the upper left corner is origin, so its coordinates are 0,0. 100 pixels to the right of the upper left would be 100,0. 100 pixels below the upper left corner is 0,100. Because our canvas has a width of 400 pixels and a height of 400 pixels, the bottom right corner would be 400,400.

Creating the draw_background function

We are going to need this function soon. It will draw a solid color onto the canvas.

The draw_background function will have three lines:

- Clear the canvas. Erase everything in a rectangle from 0,0 to 400,400 (or canvas width, canvas height).

- Set the color of the “paintbrush”. Colors in JavaScript are set using hexadecimal color codes, which store a color’s RGB (Red, Green, Blue) values in a shortened format. All color codes must have a

#in front of them. I chose a greenish color (which has a hex code of#1EBA00) for the background. Here is a color picker that you can use if you want to change the color (click on the box to select a color, and then it will generate a hex code for that color) : . - Draw a rectangle that covers the entire canvas.

Here it is. Add this function to the script:

You can see that canvas.clearRect and canvas.fillRect have four arguments. They are (upper left corner of rectangle x position, upper left corner of rectangle y position, width of rectangle, height of rectangle).

Creating the init function

When we created the web page for the game, we added onload="init()" as an attributes to the <body>. If you have a JavaScript function that needs to be run as soon as an element on the page loads, you can use the onload attribute. So onload="init()" tells the browser to run (call) the JavaScript function init() as soon as the body is loaded. Here it is. All it does is draw a background and message onto the canvas:

Again, feel free to change the color code #FFFFFF to something else if you want to: .

Also, you can probably figure them out but the basic arguments for fillText are (text, left side of text x position, left side of text y position).

Make sure you’ve added all these functions and variables to your project file (game.html). It should look like this now (with or without the comments):

And after you load the file into your web browser and open your console, you should see this:

Congratulations! You may have just written your first piece of JavaScript that does something visible on a web page!

Detect key presses

We need to detect key presses and take action when someone presses the up arrow, left arrow, or right arrow.

To do this, we simply “attach” a key_pressed function to the documents onkeydown attribute, so that when a key is pressed down, key_pressed is called. Add this to the script, near the top:

document.onkeydown = key_pressed;

JavaScript lesson: IF statements

If statements are used when a program needs to do something ONLY if a condition is true. If the condition is false, then the action is not carried out. The basic syntax (layout) for an if statement in JavaScript is:

if (this is true) {do everything in here}

You can optionally extend it and also give it something to do IF (and only if) the condition is false:

if (this is true) {do this} else {if its not, do this}

You can put anything inside the parentheses as long as it can be true or false. Everything with a value is considered true in JavaScript, so 43 and 1 are considered “true” by JavaScript. 0 is considered false.

Often you’ll need to compare to values in JavaScript, to see if, for example, one value is greater than, less than, or equal to another. In that case you’ll need to use comparison operators; some examples are == (equal to), < (less than), > (greater than), and != (not equal to). There are also logical operators which are && (and), || (or), and ! (not).

Here is an example in JavaScript, given three variables named happy, sad, and name:

Be very careful not to confuse = with ==. If you use an assignment operator (=) where you meant to use a comparison operator (==) it will result in strange unexpected results.

Create the key_pressed function

When a key is pressed, key_pressed will be called with an argument that contains more information about the key press. That argument will have a property (variable) named key that will contain the name of the key.

So we need to check what key it is and then take action based on that. But how can we check which key it is? We need an if statement!

Here’s the function:

For now, every time you press one of the arrows it will just log it on the console. Later, we will make the key presses actually do stuff.

Try it out! Reload the page in your browser, open the console, click on the green canvas, and then try pressing the arrow keys. You should see the console logging them.

Just in case you got lost, here’s what your project file should look like now.

Creating the Game Loop Function

The game loop function, or update function, will run many times per second and each time it runs it will calculate the new position for all the colored dots, and also check to see whether the player’s position is over a dot or not. Then it will clear the canvas and redraw the scene.

It is important to clear the canvas each time or else every pixel that is drawn will just layer on top of the previous ones, creating an ugly mess where there are a ton of dots overlapping one another.

Before you start, though, you’ll need to create some more variables, including one type that you haven’t learned yet.

JavaScript lesson: Arrays

Arrays are simply lists of variables, all stored within another variable.

For example, say you have a list of ages that you need to store in variables. You’re not exactly sure how long the list will be, but even if you did, it would be very long. So obviously manually creating lots of variables like this:

let age1 = 16;

let age2 = 87;

let age3 = 33;

let age4 = 12;

...

is not an option. The solution is to use an array, which can store any amount of numbers, strings, or other objects in a way that you can easily access them but they don’t all have to have variable names. Array syntax is simple: let my_array = [values, separated, by, commas]

Here’s how you would store the above ages in an array:

let ages = [16, 87, 33, 12, ...];

And then you can access the ages with the syntax ages[i], where i is an index that identifies what value you want. Because in programming, counting always starts with 0, to get the third value in the array you’d use an index of 2:

ages[2] is equal to 33.

I’ll say more about arrays later.

Creating some variables

For our game to work, we need to create some variables (and arrays) that we will use later. Add these to the top of the script.

First we will create variables to store the player’s x and y coordinates:

let player_x = 200;

let player_y = 220;

Then arrays to store the coordinates and colors for all the colored dots created. The arrays will have one dot at the start of the game:

let dots_x = [200];

let dots_y = [0];

let dots_color = ["#800080"];

And a variable to store the score:

let score = 0;

And a variable to store the time that the game started at:

let start_time = 0;

And a variable to store whether or not the game is finished (0 or 1):

let game_over = 0;

It’s always good to make your program as easy to customize as possible, so lets create a few “settings” variables so that we can easily change them instead of looking for a certain line or lines in our code. First some color ones:

let dot_color_options = ["#FF0000", "#800080"];

let player_color = "#FFFF00";

let text_color = "#FFFFFF";

Here’s the color picker in case you want to choose different ones: . Also feel free to add more options to the dot_color_options if you wish.

Now for a frame rate (in FPS or Frames Per Second) - the number of times update is called in each second. To be safe, we’ll keep the frame rate relatively slow:

let frames_per_second = 15;

And a variable to define how many pixels each dot should move down the canvas, per frame.

let dot_pixels_per_frame = 5;

player_y MUST be a multiple of dot_pixels_per_frame. Here we are safe because 220 divided by 5 is a whole number.

Then add a variable to specify how many pixels the player should move when the player presses left or right:

let player_move_increment = 40;

player_x MUST be a multiple of player_move_increment. You will see why later on. Here we are safe because 200 divided by 40 is a whole number.

Also we need to specify how far apart (vertically, in pixels) each dot should be, and how long (in milliseconds) the game should be:

let dot_distance_apart = 10;

let game_duration = 30 * 1000;

(30000 will create a 30 second game)

Then the radius for the (circular) player and dots:

let dot_radius = 10;

let player_radius = 20;

That’s all for now!

The update function layout

Here’s the plan for the update function:

Add it to the script in your project file. We will replace the comments with code over the next few sections.

Making the loop run & keep track of the time

When the player presses the up arrow, the update function should start looping.

But before we start looping the update function, we need to store the time that the game started so we can compare it each frame and see if the difference between the time that frame and the time at the start is greater than the time limit (stored in game_duration). If it is, the game will stop.

To store the time we can use the Date class, which has a ton of functions for managing time. We can use the start_time variable we created to store the time the game starts at. new Date().getTime() creates a new Date class and then uses it to get the time, in milliseconds, since January 1, 1970.

To start looping the update function, which effectively starts the game, we can use setInterval(arg1, arg2) which is a function that runs a certain function (first argument) every x number of milliseconds, where x is the second argument.

But we need to ensure that the game hasn’t already started whenever we try to start it, because if we didn’t check to ensure game hadn’t started, then pressing the up arrow a second time would reset the start_time and make the update function run twice as often, which would result in unexpected behaviour.

We can check using the start_time variable, which is set to 0 when the page loads - so we know that if start_time is not 0, the game has already started.

We can add all this in the key_pressed function by adding the following to the if (key.key == "ArrowUp") block, below the console.log, so that it is run when the up arrow is pressed:

We divide 1000 by frames_per_second to get the interval (in milliseconds) that we should pause between each call to update. If, for example, frames_per_second was set to 5, then 1000 divided by 5 is equal to 200, and 200 milliseconds is one fifth of a second, so the function update would be called five times per second, which would result in 5 frames per second.

Add the first if statement

Let’s add the if statement that checks to see whether the game’s time limit is up yet. If it is, it sets game_over to 1 (true). Here’s the updated update function:

Again, just in case you’ve gotten lost, here’s what your project file should look like now (excluding comments).

JavaScript lesson: for loops

for loops are most commonly useful in two scenarios: When you want some code to run a certain number of times, or else when you want to iterate through every item in an array and do something to each one.

The basic syntax for a for loop is for (before loop starts; condition to continue; after each iteration) {code block; do something;}. Here’s an explanation:

A for loop runs the code in the code block (the code between { and }) over and over again as long as the condition, or the second statement in the parentheses, is true.

At the beginning of each loop, the for loop checks the condition - if it is true, then the code block is executed. If it is false, then the code block is not executed and the program continues with the rest of the code. Whenever the code block is finished running, the for loop executes the third statement inside the parentheses and then goes back to the beginning and checks the condition again.

Before starting the first loop, the for loop will execute the first statement in the parentheses. The third and last statement in the parentheses will be executed every time after the end of the loop, before going back to the beginning.

Here’s an example of using a for loop to run some code 5 times, and then using a for loop to iterate through every item in an array:

Here’s the expected output (on the console):

Right now, i is 0

Right now, i is 1

Right now, i is 2

Right now, i is 3

Right now, i is 4

Next Example!

16

87

33

12

Clear Canvas, Move dots Down Screen & Draw Them

We will start by programming the part of the update function that is not within the if/else blocks.

First we clear the screen using our draw_background function.

Then we use a for loop to move each dot down the canvas a bit and draw it.

Drawing a solid circle on a canvas is somewhat tricky - you need to draw a circle and then fill it in. Here are the functions we’ll use to do that:

canvas.beginPath();

canvas.arc(x, y, radius, start angle radians, end angle radians);

canvas.fillStyle = color;

canvas.fill();

canvas.closePath();

When we draw the arc, angles are in radians, so one full 360 degree turn is 2*pi.

Arrays dots_x, dots_y and dots_color are used to store the x and y positions and colors for all the dots, so that the same position or color in each array corresponds to the same dot. For example, dot number 5’s x position will be dots_x[4] and dot number 5’s y position will be dots_y[4] and dot number 5’s color will be dots_color[4]. So we can use these arrays to get the info we need about each dot.

Here’s the code. Replace the corresponding comments (the clear screen, move, and draw dots ones) in the update function with it:

Draw player onto screen

Drawing the player is just like drawing the dots. But before we draw the player, we need to make sure that its x position is within the the canvas (0 < player_x < canvas width). We can clamp the number within the range by using JavaScript’s maximum and minimum functions:

player_x = Math.max(0, Math.min(player_x, canvas_element.width))

Replace the corresponding comment in the update function with the code.

Draw score

The last thing to draw is the score, into the upper left corner. Replace the comment with the code:

Test it

OK! We have all of the update function finished now except for the if/else blocks. This is what it should look like:

And this is what it should look like if you open the game in your browser and press then up arrow:

You can see the single dot, the score in the upper left, and the yellow player. However the score doesn’t change yet, and you can’t move the player.

Moving the player

Let’s make the player move.

We need to add a part to the original key_pressed function that changes the player_x variable when the left or right arrows keys are pressed. Here’s the updated key_pressed function:

player_x -= player_move_increment is the same as player_x = player_x - player_move_increment.

Try it out in your browser and you’ll see that you can move the player left and right with the arrow keys, but you can’t move the player off the sides of the canvas!

Check to see whether Player is over a dot

Now for the part inside the if block.

To check whether a player is over a dot, we can use a for loop and compare the player’s coordinates to each dot’s coordinates.

Replace the corresponding comment in the update function with this code:

Try it out in your browser and you’ll see that, when the player “flies over” the dot, the score in the upper left changes to 2.

Generate new dots at top of screen

Obviously the game needs more dots. So let’s create more - it should be as simple as adding new items to the dot arrays (dots_x, dots_y, and dots_color).

However we can’t create a new dot every frame, or else the canvas would quickly become filled with hundreds of dots, making the game way to easy. So each frame we need to check and make sure the distance between the top of the canvas and the highest dot is greater than dot_distance_apart. This is very easy, using an if statement.

When we generate a new dot we also want it to have a random x location, and a random color (chosen from the array of color options). We can do this by using the Math.random function, along with some other Math functions.

Math.random returns a number between 0 and 1 so that the number is greater than OR equal to 0 but the number is always less than 1. So to get a random choice from an array (like the dot_color_options array) we can multiply a random number by the number of items in the array and then round it down to the nearest integer (we can just nest the functions within each other):

dot_color_options[Math.floor(Math.random() * dot_color_options.length)];

Math.floor(number) returns a number rounded down to the nearest integer. In this case, the number is Math.random() * dot_color_options.lenth - a random number multiplied by the number of options in the dot_color_options. The rounded down number is then used as the index to retrieve a random item from the dot_color_options array.

Generating the new x position is not as simple as it seems because we must make sure that each dot falls into a position that the player can access. There are only 400 (the width of the canvas) divided by player_move_increment (the distance that the player jumps to the left or right) horizontal positions, like “lanes”, that the player can possibly be in on the canvas (plus one, on the far right side of the canvas). The total number of x positions (400) is far greater than the number of x positions the player can be in, so if the dots were assigned to any of the x positions the player wouldn’t be able to “fly over” most of them. We have to make sure that a new dot’s x position is one that the player can be in.

So we must multiply a random lane number (an integer between 0 and canvas width divided by player_move_increment + 1) by the player_move_increment to get a new x position for the new dot:

let lane_number = Math.floor(Math.random() * (canvas_element.width / player_move_increment + 1));

let new_x_position = lane_number * player_move_increment;

We can use the array.push(item) function to add an item to the end of an array. We can use this to add the new dots. The most recently created dot, which is the highest dot on the canvas, will be the last item in each of the arrays (dot_x, dot_y, and dot_color) because each new dot is added to the end of the array. Therefore we can use dots_y[dots_y.length - 1] to get the last item in the dots_y array (remember we must subtract one from the array length because in an array the index of the nth position is n - 1).

Here’s the code. Replace the corresponding comment in the update function with it:

Game Over Screen

Finally! The last part!

The game over screen is simple to program. Add this to the bottom of the update function:

Finished game!!!

Finally, the game is finished!!! The final code is:

And here is a gif of a ten second game:

And here is the actual game to play!

Improvements

Here are some improvements that could be made to the game. I’ll leave it to you to figure out how to implement them:

- Dots disappear when you fly over them (right now, they continue down the canvas even if the player has flown over them). Hint: Look up a JavaScript function to remove an item from an array.

- Page looks nicer. Hint: maybe go and learn some CSS so you know how to style the web page.

- “Play again” functionality. Hint: You might need a function to reinitialize all the variables. At the very least, you could set it up so that the

rkey reloads the page. - High score system. This one is tricky to implement with just a file and browser, because many browsers block cookies and local storage (which are the best option for creating a high score system) from local files. You could look into putting your web page online and then try it.

- Better looking player and dots. You could look up how to display an image instead of a circle on a canvas, and then replace the circles with custom-designed characters.

- Better player-over-dot detection. Right now, the player has to be exactly centered over the dot for the game to detect it. It would be nice if there was a margin so that it was a little easier to get points. Hint: change the

ifstatement condition so that it checks whether the distance from the player’s coordinates to the dot’s coordinates is less than a limit you set. - Add a form to the web page so that the player can change the settings (e.g. the colors, game duration, etc.) before the game starts, as opposed to the hardcoded settings. Hint: research HTML forms and then look up how to read form input using JavaScript.

- Enemy dots. Add dots that are a different color or shape that reduce the score when the player touches them, instead of increasing it.

- Phone support. Right now, you can’t play this game on a phone because phones don’t have keyboards with arrow keys. Try adding two on-screen left and right buttons that trigger the same actions as the arrow keys. Hint: look up how to add HTML buttons that trigger a JavaScript action.

There are so many more enhancements you could make. Your imagination is the limit!

Conclusion

Congratulations! You’ve done it!

I hope you learned lots and had fun building this game. Thank you for reading my article!

If you need any help with this project, feel free to contact me!

Please leave any questions, comments, feedback, or suggestions in the comments below or else contact me.

More Resources to Learn JavaScript

To find lots of good JavaScript tutorials, just google js tutorial.

W3 schools is also a great website for learning about HTML and JavaScript. Here are links for every concept we used: